If you’ve been wanting to know more about the cardinal virtues, then you’re in the right place. This article will do the following:

(1) Explain the overall definition of cardinal virtue

(2) Define and describe each of the four cardinal virtues

DEFINITION OF CARDINAL VIRTUE

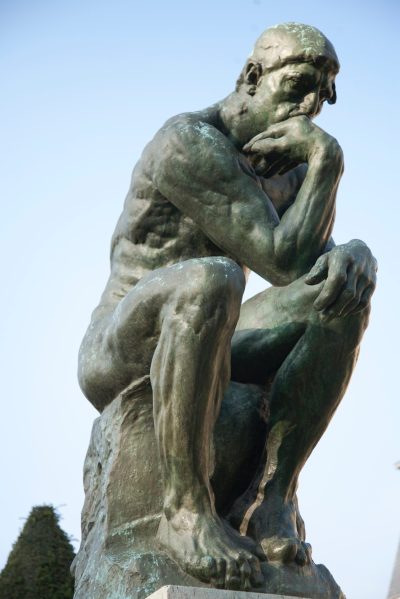

So, what is a cardinal virtue? To start, let’s first define a virtue. A dictionary definition of virtue is “the quality or practice of moral excellence or righteousness.” As defined by the Catechism of the Catholic Church, virtue is “a habitual and firm disposition to do the good.”

A virtue then is a basic building block of morality, characterized by habitual striving for moral goodness. By practicing virtue, one becomes stronger in virtue, becoming more likely to resist evil and temptation. In this regard, a virtuous person forms a strong sense of habitual right thinking.

What then is a cardinal virtue? No, it is not the virtue of being a red, midwestern bird—a cardinal (although I suspect the bird and the virtue might be connected in a roundabout way, but I digress).

The core word of the term cardinal is the Latin cardo, which means hinge. This word describes the relationship between the four cardinal virtues and other virtues: all the virtues “hinge” upon the cardinal virtues. In other words, the four cardinal virtues are the foundation of all moral virtue.

There are four cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance. These four virtues are also called natural or human virtues, and any person can pursue them through reason and logic. Saint Thomas Aquinas—a prominent philosopher—describes these four principal virtues in a particular logical order (the order listed above) for a reason.

This order described by Thomas Aquinas helps us better understand the cardinal virtues as a source of practical wisdom and a set of guiding principles to help each of us be a good person and have a fulfilling life. Let’s take a look:

PRUDENCE – THE FIRST OF THE CARDINAL VIRTUES

Prudence is the first of the cardinal virtues because it is the basis of all good morality. Moral goodness and prudence are inherently intertwined: a prudent act must be morally good, and a morally good act must be prudent. In fact, prudence dictates the moral goodness of any act. Since all virtues aim for moral good, all moral virtue must conform to prudence. In essence, prudence is the basis of all moral virtues.

Definition of Prudence

Prudence is seated in the intellect, meaning the cardinal virtue is exercised in the mind. The mind is the first stage of any action; you must first think about and decide what to do before you do it. You can think of prudence as the first step of any morally good act. Prudence guides our thought process to exercise moral virtue and produce good acts.

There are three key aspects of prudence. By definition, prudence is the ability to (1) correctly discern good from evil, (2) choose good over evil, and (3) seek good through good means. Let’s unpack this definition, piece by piece.

Prudence Part 1: Correctly Discern Good from Evil

In order to do good, one must first know what is good. So a natural question arises: how does one know what is morally good versus bad? How does one know what is prudent?

Legality vs. Morality

The laws of society could be a decent place to start. For example, theft and murder are illegal and punishable by law. Both theft and murder are also immoral acts. So far so good for the law being prudent.

What about cheating on a spouse or lying to your coworkers? Neither of these acts are necessarily illegal, but they are surely immoral and imprudent. These examples draw out an important distinction between legality and morality. Just because an act is legal does not meant that it is necessarily morally good.

Also, the correlation between legality and good morality is contingent upon the moral code of society. A morally loose society will not have a set of prudent laws, for example.

The Conscience as an Innate Moral Compass

So, if society’s laws are not a complete guide for prudent acts, then where else can we turn. Hmm…the conscience perhaps. Our natural intuitions generally agree with prudence in extreme cases. For example, most people—thankfully—have a strong aversion to murder. This just feels wrong, so most never do such a thing. Most people practice prudence and refuse to engage in this act.

You could contend that people only avoid murder because they don’t want to get caught and go to jail, but I think this moral inclination is deeper seated than just fear of punishment by the law. Most people would be unable to commit murder; they would feel deeply disturbed and repelled by even the thought of murder because their conscience would correctly tell them that murder is a grave evil.

Source of Moral Compass?

What is the source of this moral compass though? Is it learned? Is it innate? I think there is an innate nature to morality. A sort of hardwired sense of morality, you might say.

But what about more gray areas, something not so black and white, not so extreme. Consider if someone left a twenty dollar bill behind in a classroom, and everyone has already left. Would you take it for yourself, or would you try to find the owner? Would your decision change based on the amount of money? What if it were only a one dollar bill? What is the prudent thing to do here?

You could easily rationalize the situation and convince yourself to take the money. “They probably won’t even notice.” “Finders keepers.” “They should have been more careful. Too bad for them.”

Notice how people can become misguided about what is good versus evil. The exact right thing to do is not always so clear. Sometimes, people can rationalize an evil to be “not that bad.” Or worse, they can confuse evil for good.

Ethics and Religion for a Well-Formed Conscience

In the case of moral ambiguity, it is critical to have a well-formed conscience. But how?

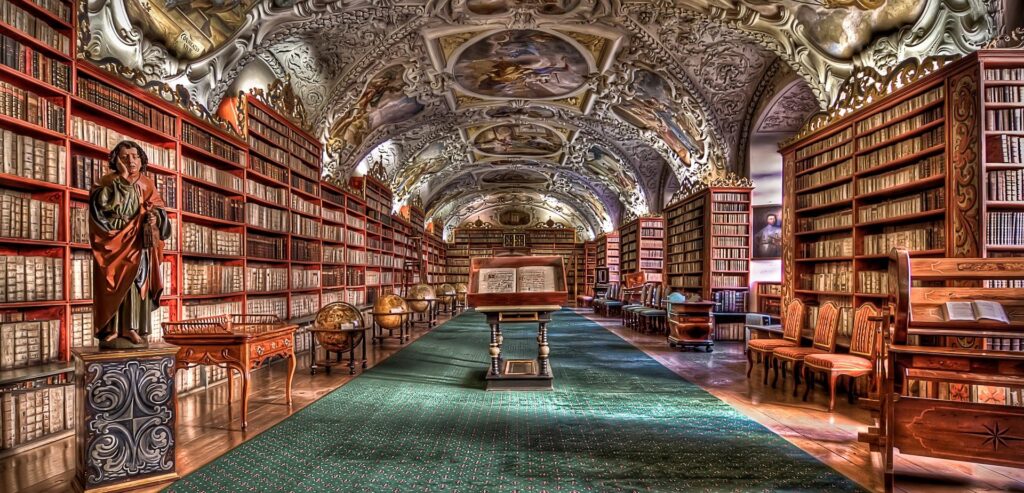

Well, there’s an entire branch of philosophy called ethics, which considers entire systems of moral virtue ethics. Many thinkers have contributed to this philosophy throughout history, and it’s worth studying to help inform your conscience and develop a consistent set of moral values.

Religion also engages in ethics, and several religions are thousands of years old. As such, religions have had many prominent thinkers contribute to understanding ethics and how it pertains to everyday life.

Furthermore, in the case of moral ambiguity, it is necessary to have a solid moral authority to inform the conscience. Religion fulfills the role of moral authority and can be extremely helpful in forming a well-developed conscience through teachings and knowledge. As a moral authority, religions can offer much understanding of morality. As an example, the Catechism of the Catholic Church was extremely helpful in furthering my understanding of the cardinal virtues to write this article.

In sum, a well-formed conscience is critical in discerning good from evil, and it can be helpful to learn religions and ethics to inform your conscience.

Prudence Part 2: Choose Good over Evil

So you have discerned good from evil with your well-formed conscience. But now you are faced with a choice: do you choose good, or do you choose evil?

Unfortunately, people do not always choose good over evil, even after they have correctly discerned good from evil. In fact, human beings have done evil acts throughout all time and will continue to do so until the end of time. But why?

Luckily, I think it’s rare that someone chooses evil for its own sake. Usually there is some empty, near-sighted promise that they seek in the evil act—a false sense of justice in murderous revenge or an urge to satisfy an impulsive desire, for example. Or perhaps someone simply fails to conquer fear of ridicule or retaliation for standing up for what’s right. The reality is that human beings often fall short of choosing good, despite knowing what is good. People act in such ways because they give in to temptations or cave to adversity and pressure.

A prudent person chooses good over evil, but that choice is often not easy. To avoid falling prey to temptation and adversity, other cardinal virtues are helpful (see discussions on temperance and fortitude later in this post).

Prudence Part 3: Seek Good through Good Means

Let’s say you correctly chose good over evil. Good! (Is that a pun?). But now the next task is seeking a method of achieving that good. Here some people may become misguided. A good end can be achieved in a wrong way. For example, let’s consider stealing from the rich and giving to the poor (a la Robin Hood). The end goal of giving money to the poor is a morally good act. However, stealing is morally wrong.

Showcasing Prudence

There are several good illustrations of prudence in the entertainment lore. To solidify your understanding of the first of the cardinal virtues, check out this post for a showcase of prudence by none other than the Batman.

JUSTICE – THE SECOND OF THE CARDINAL VIRTUES

Of the four cardinal virtues, justice is likely the most recognizable by name. Indeed, people encounter the word justice quite often. Justice is a colloquial term, especially compared to the other virtues. In fact, modern societies have an entire system that bears the name—the justice system—and this system features in various news cycles, locally or nationally. People may use the term justice frequently, but what does justice really mean?

Definition

Simply put, justice is the proper allotment of what each person deserves. This begs a couple of questions: how do you know what is the “proper” allotment, and what does each person deserve? These are good questions, and one must know the answers to these questions before exercising justice.

Prudence Guides Justice

Fortunately, we have the first cardinal virtue—prudence (see section above)—to inform the answers to these questions. By exercising prudence, we know through intellect what is good, ultimately choose the good and select a good path for achieving the good. Got it? Good.

Notice, though, that all of prudence is exercised within the mind, within the intellect. These decisions in intellect must be willed into action to take effect. Justice—seated in the will—fulfills this role and is the application of prudence. For this reason, justice is second to prudence: one must practice prudence before exercising justice. Through prudence, we know what is the proper allotment and what each person deserves.

Justice – What Each Person Deserves

Let’s unpack the definition of justice a little bit, focusing first on “what each person deserves.” When discussing what each person deserves, it’s natural to arrive at a discussion of someone’s rights. While prudence informs what these rights are, justice is charged with protecting them.

Natural Rights and Legal Rights

According to the Meriam-Webster dictionary, a natural right is a “a right considered to be conferred by natural law.” John Locke is famous for describing the right to life, liberty and property, and the Declaration of Independence—based on Locke’s ideas—describes the right to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness as inalienable rights. These are good examples of natural rights.

Justice pertains firstly to securing natural rights (right to life, liberty, property, human dignity, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, etc.). Secondly, justice pertains to securing legal rights (contracts, agreements, jurisdiction, etc.). However, securing natural rights supersedes securing legal rights, if ever there is a conflict between the two.

Protecting Rights

The cardinal virtue of justice deals with protecting these rights, ensuring that each person receives what they deserve. “Protection from what?” you might ask. Unfortunately, people need protection from other people. For example, consider the crimes of theft and murder. With theft, the thief violates someone’s right to property, and with murder, the murderer violates someone’s right to life. These crimes are injustices because the victims’ rights were not protected; they did not get to keep their property or their lives, which they rightly deserve.

Justice is positive in protecting people’s rights, despite the common misconception that justice is strictly punishment of evil doers. Recall common phrases describing justice as criminals “getting what they deserve,” “serves them right,” “justice is served,” poetic justice, etc.

Punitive Justice

Punishing evil doers is more properly described as punitive justice (root word: punishment). This is still justice because the punishment of the evil doer (jail time and removal from society) protects the rights of others. The evil done was violating the rights of others. By punishing the criminal and removing them from society, potential victims are protected from the criminal, in turn securing the rights of the victims and potential victims.

Justice – Proper Allotment

Punitive justice is about proportionality as well. The punishment must match the crime. This is what is meant by a “proper allotment of what’s deserved.” Consider a shoplifter that has been apprehended and submitted to the justice system. The criminal deserves punishment for her crimes in order to deter continued theft and protect the property of others. However, to sentence the shoplifter to life in prison would not be proportional to the crime committed. This excessive punishment would be unjust. Deciding what punishment is appropriate for the crime again requires prudence, and is the purpose of any justice system.

Showcasing Justice

Justice is portrayed quite often in the entertainment lore. To showcase a just cause, it’s only natural to discuss the Dark Knight and his fists of justice. Check out this post showcasing justice through the lens of Batman.

TEMPERANCE – THE FOURTH OF THE CARDINAL VIRTUES

Temperance is the fourth of the cardinal virtues because it serves the other three cardinal virtues. After choosing the right path to achieve good (exercising prudence), willing this decision into action (exercising justice), and persevering through external resistance (exercising fortitude), one must persevere against internal temptation (exercise temperance). The virtue of temperance is moderation in all things, rising above desires and passions.

Definition of Temperance

Temperance is ultimately constant self mastery that resists disordered passions from within ourselves. Temperance dictates moderation of good things and avoidance of bad things.

Exercising temperance helps overcome disproportionate and disordered physical desires. For example, food is good and even necessary, but only in moderation; excessive eating is bad, called gluttony. Similarly, alcohol is fine occasionally, but repeated over indulgence in alcohol is bad, called alcoholism. Sexual desire is natural, but beyond proper bounds, it is bad, called lust. Temperance dictates balance.

Temperance overcomes not only base physical desires (like those listed above), but also non-physical desires like vain glory. For example, it’s good to keep up one’s appearance and desire a healthy body; however, it’s bad to obsess over your appearance to the unhealthy extent of body dysphoria such as anorexia or bulimia. This disordered desire to look a certain way is unhealthy, and exercising temperance would help us avoid this damaging desire.

With internal passions restrained through temperance, one more easily exercises the other three cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, and fortitude.

Showcasing Temperance

Keeping with the running theme here, Batman is a good example of self-mastery and temperance. Click here to read this post using Warner Bros. Batman Begins to showcase temperance.

Conclusion

In summary, cardinal virtues are the basis of good morality and the root of all other virtues. There are four cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance.

Prudence – First cardinal virtue

Prudence is the mother of all moral virtue and consists of three key aspects. To exercise prudence, one must (1) correctly discern good from evil, (2) choose good over evil, and (3) seek good through good means.

Justice – Second cardinal virtue

Justice is the proper allotment of what each person deserves. Prudence guides justice by dictating what qualifies as “proper allotment” (sentencing proportional to a crime in punitive justice) and “what each person deserves” (protection of someone’s natural rights).

Fortitude – Third cardinal virtue

Fortitude is the ability to resist external forces in opposition to exercising prudence and justice. Such external forces can include physical assaults, verbal assaults, dread, fear, and anxiety.

Temperance – Fourth cardinal virtue

Temperance is the ability to resist internal temptations in opposition to exercising prudence and justice. Such internal temptations are usually self-indulgent temporal pleasures, such as gluttony and lust.